The Challenge of Postmodernism

Date added: 2023 May 8

Last modified: 2023 May 8

The 60s to 80s were a confusing time. In the U.S., these years are perhaps most significant for their association with the Civil Rights Movement and subsequent radicalism. The U.S. went to war in Vietnam, experienced stagflation, turned towards Neoliberalism, and emerged the victor in the Cold War. Outside of the U.S., there was the growth of the New Left movement in the first world, the second world fragmented in the Sino-Soviet split, and third world decolonial movements rose elsewhere.

For many of us born afterwards, this era has a certain nostalgia to them. In our imagination, this era plays in black and white, and the memory of famous figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Che Guevera, and others loom large. This era was one of turmoil and chaos, yes, but it was also a time of change and in many ways, progress, something rare indeed. The experience of the 80s laid down a legacy that much of us take for granted, and perhaps may even provide some of the ideas that might help us out of our impending crises, including the big two: Resurgent Fascism and Climate Catastrophe.

For example, Black Lives Matter (the movement, not the organization) is a popular movement of racial liberation with no recognizable leader. I remember when I was younger thinking that surely this lack of leadership was a weakness or mistake. But put in context with the 60s, where leaders of popular movements were assassinated, the choice of BLM to forgo leadership in order to make it impossible to destroy in a headstrike at the cost of greater disorganization made me appreciate the rationale.

In the humanities, especially in history, sociology, and anthropology, the 70s and 80s were particularly significant. Much of the current day’s research methods, techniques, and ideas were directly the result of the movements in the 80s and their ideas. Broadly, this is referred as the Cultural Turn. Some go as far as to label the 80s as the beginning of the Postmodern era.

Big words and not very informative, I know.

Though these terms are opaque, these are important and worthwhile ideas, and not many of us have internalized them. That may be due to academic-popular cultural lag or the slipperiness of these concepts, but upon understanding them, these hopefully provide much needed solace and concepts for dealing with the clusterfuck here and headed towards us in these coming years.

Modernism, Postmodernism, and Unhappy Scientists

Though I work in science and STEM, I feel an unease talking with many fellow people in those fields. There’s an undercurrent of Modernism in the way they talk (to be defined later). STEM fields, built upon Modernist ideas and concepts, are fairly rigid in how they conceive of the world. For example, many people in STEM conceive of history as a constant march of scientific progress or improvement. They might even hold problematic views such as the colonization of the Americas was inevitable.

For many scientists, they take comfort in being able to explain everything by some overarching theory. There are many of them who gravitate towards Jared Diamond’s famously hated (and truly terrible) book Guns, Germs, and Steel.1 I say none of this to disparage scientists or tech workers, especially since, again, I am one of them, but to make an internal critique of this mindset that is too prevalent.

Modernism

What I have said immediately above is roughly the idea behind Modernism: that there is a (grand) theory that can explain everything.2 Part and parcel with that central idea of Modernism is the championing of categorization, that everything can be discretized into useful, meaningful distinctions.

Physical Science is premised upon these ideas. Math has the ZFC axioms from which the rest of mathematics builds upon. Physics is focusing on a “Theory of Everything” which seeks to unify current theories of gravity and quantum mechanics. Biology has such problems such as the Central Dogma and the Protein Folding problem to discovering the origins of life. Medicine seeks to cure or treat every illness or affliction.3

This approach or goal has been very fruitful for Physical sciences. Pursuing a unified theory for everything has absolutely paid off. We would be worse off if not for Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, Germ Theory, Genetics, Computers, etc.

There’s just one problem: these ideas are harmful when directed at social issues or social scientific fields, and the firm foundation of physical science is much more insecure than most scientists believe.

Not Anti-science

What I’m saying may set off alarm bells for most STEM workers. It may sound like I’m about to spout off anti-science ideas. I am not. Again, I am a STEM worker. But if we examine science very closely, there are a few coherency issues.

Take mathematics. Math is a rigid and axiomatic field. That basically means it relies upon agreed upon sensical agreed upon truths called axioms, and reasons strictly from those to build up the rest of everything. The axioms that underlie most math today is called the ZFC axioms, and they are thus the foundation of mathematics.

Unless you get deep into mathematics history, you may not know that math nearly faced collapse in the 20th century. For a while, there was a raging debate within mathematics, between Intuitionists led by L.E.J. Brouwer (who gave us Brouwer’s Fixed Point Theorem, one of the most important theorems in math history) and Formalists led by David Hilbert (known as the last person to know math. David Hilbert contributed to every field of math at the time, and had an unshaking faith in it). The debate was over the problems surrounding the foundations of math. At the time, math was not systematized or axiomatic as it is today. Back before the 1900s, people did not argue from a common set of axioms or foundations. A lot of ideas and theorems were floating out there in the aether, vaguely considered true since enough people believed that they must be true. Only in Geometry was there an axiomatic approach, and this is largely because of the influence of Euclid’s Elements.

Mathematicians, being mathematicians, could not be satisfied with the lack of rigor, so for several decades they spent their efforts putting the field on firm foundations. Basic ideas like functions and calculus were made rigorous. At the time, the limit definition of derivatives was new, replacing the former idea of infinitesimals that calculus used to rely upon. The Bourbaki school, a group of mathematicians famous for their (confusing) level of rigor, came to prominence at this time. The famous Bertrand Russell began work on an intended masterpiece of math, the Principia Mathematica, that would finally put the entire field on common founations.

But at the time of this program, there appeared nearly unresolvable problems. For example, Bertrand Russell discovered a paradox that nearly destroyed the Formalist position. Their position was only saved by simply restricting away the paradox in some basic mathematical definitions. Yet the Formalists ultimately lost as the Halting Problem, and worse still, Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem was published.

The Incompleteness Theorem proved, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the Formalists were wrong. Nobody can rigorize math. There always exist problems unresolvable outside of any set of axioms. There always exist unsolvable problems. Mathematicians have largely shoved this horrendous conclusion underneath the bed, pretend it doesn’t exist anymore, and let Set Theorists and Logicians deal with it. But its getting harder to ignore. Some recently solved problems, like the Continuum Hypothesis were proven to be these unresolvable/unprovable problems.

If that was dizzying, basically what I’ve said is that not even math, the field that prides itself on logical rigor, can prove everything. We have proven, in math, that there cannot be a Grand Theory. Math is always incomplete, some statements beyond the current set of foundational axioms we have for logic.

But Physics may also suffer from the same problems. Their current search for a Theory of Everything is proving fruitless. String Theory, probably the most reasonable answer for a Theory of Everything, doesn’t seem to be bearing fruit. Some have proposed that it is even Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem that is responsible for the prevention of a Theory of Everything in Phyics.4

In biology, epigenetics might challenge the Central Dogma, as environmental factors can now affect DNA. In other fields such as Medicine or Psychology, there is currently a replication crisis, as key results and papers turn out to be irreplicable.

The concept of Science itself is not as rigid and complete either. There are many forms of science.

And even now, though, again, I am not Anti-science, that there is an anti-Science movement at all suggests there are problems out there that science has not sufficiently addressed. We have not even begun to discuss those times science has been used for eugenics and racist sterilization, war, imperialism, leaded gasoline, sugar industry coverups, etc.

Remember that Science is an institution for discovery, but like all institutions, it does not make it immune to problems. Science has never been very good at communication, and the institution needs external factors to contribute to it, such as funding and political support. Perhaps the most important recent idea regarding science is that the only real difference between it and the Facebook Karen who does ‘research’ is that there’s a set of institutions that support and reinforce true discoveries that gives what Scientists say extra force of truth.5 This might seem like a weak conclusion, but it’s probably the most honest. And this idea, that people’s anti-Science stance is their misunderstanding of the institutional background, is a real method for countering anti-science stances, by arguing on the strength of one’s institutional position rather than superior knowledge.

Social Sciences and Grand Theories

Hopefully you begin to see the insecurities that plague science. But in fact, these issues may themselves be a result of Modernism itself, an issue with Grand Theories themselves.

In social sciences, grand theories used to be all the rage. They’re still sometimes famous, though universally opposed in academia.6 You’ve certainly heard of some before. For example the liberal theory of progress: we are working towards a better and improving future, and though there are dark moments, we will always obtain a better world. Many of your parents believe this one. But there’s others: Social Darwinism conceives of history being a struggle of survival of the fittest, including the social realm and between civilizations. The Clash between Civilizations narrative is largely false and overblown. Civilizations don’t have emotions nor care about clashing, they just happen to. And the rich in society are only there because they were born rich or got lucky, not because they are superior in some biological way. Also, if life is survival of the fittest, it is likely that cooperation, altruism, mutual aid, and kindness are actually the fittest lives.7

Another famous grand theory is the Marxist stages of society: Primitive, Slave, Feudal, Capitalist, and Socialist societies are the stages of society, and all societies must progress through them. This leaves out Marx’s incorrect formulation of the “Asiatic Mode of Production” which was ill-conceived and theoretically poor, and neglects that slave societies aren’t necessary in the sequence due to recent research, and how Capitalist and Feudal societies may not have actually been different.

You can see the theme here. For every Grand Theory in social science, it fails. It’s not true. For hundreds of years, people have been advocating for grand theories, but each one has failed the test of time. Enough have failed that it seems more reasonable that it is the other way around. The problem is not that we just haven’t formulated the right grand theories, but that grand theories themselves, these just-so stories, are the problem inherently. Having an overarching explanation of everything is wrong.

Postmodernism

This brings us to the Postmodern critique and the Cultural Turn. With all these faults of Modernism, the dramatic turmoil of the 80s made Postmodernism into a serious force in the academy, as the foundations of society were questioned. The result was that new research was jumpstarted in almost every social science field, especially in history, sociology, and anthropology.

So what is Postmodernism? If Modernism is the belief in grand theories, then Postmodernism doesn’t believe in them.8 There is no universal theory for society.

That idea might be scary for many STEM workers, but it’s not that bad. While grand theories are out, theories themselves are still fine. They are just asked to be particular - to apply to a specific time or place. They should be theories of the middle or microtheories. Another word we might call them is a model.

While grand theories are terrible, models are great. Models can be replaced and tested, and while “all models are wrong, some models are useful.” They provide some bang for their buck compared to grand theories which are always wrong but are often circular in reasoning.

One common strand of thought is cultural relativism: that every culture has its own context for its practices and beliefs and values. This doesn’t mean they can’t be critiqued, but one should try to understand its place in that culture before making a critique. This recognition is what led to the Cultural turn, the focus on meanings to cultures in the humanities.

Another common belief now is eclecticism: the choice to use several ideas or ideologies for understanding. There’s no need for external consistency since there can’t be any, so one might as well use ideas from several disciplines or theories.

One other well believed idea, at least in academia, is social constructivism - categories or concepts are societally contingent. That is unless a society recognizes an idea, it doesn’t exist. For example, gender is a social construct, there have been societies that do not recognize gender at all.9 Another is with colors, such as the blue and green distinction which some cultures lack.10

Does this mean there’s no such thing as truth? Some Postmodernists believe that. However more (I included) believe that this means what can be considered true is societally contingent, and for many societies, what is considered true is decided by who has power to some extent.

What this does free us up to do is genuinely consider the perspectives of those who have historically been marginalized, the perspectives of women, Black people, POC, colonized people, etc. Since truth is decided by the powerful, many feminist researchers allow participants to give self narratives which, while not always the most helpful for seeking out what may be a truth, deserve to be treated seriously and considered without dismissal due to the historical power imbalance. This is incredibly freeing, to be able to say what you or I or random Joe Schmoe off the street should all be considered equally.

Extrapolating far enough, we can get decidedly Postmodernist ways of organizing and conflict resolution, such as Dialogical Epistemology, which aims to solve the Oppression Olympics.11 We can find ways of prioritizing historically marginalized voices and give them a place to be heard, since nothing is more or less valuable. Value itself is possibly societally contingent. Just as society molds the values, we can mold the values alternatively.

But Postmodernism also suffers from its own issues. First off, if truth is societally contingent, then is the pursuit of truth worthwhile? Does it make sense still? For some Postmodernists, it’s basically useless. For most others, it’s fine to seek out a truth, but one cannot call it the truth. That’s not far off from how science tends to conduct itself. What is true in science is only what is not yet disproven. But for many, this ambiguity to truth-seeking becomes Nihilistic fast, and for many who initially pursued Postmodernism, they have ended up depressed or given up. What is the point, when the point doesn’t exist?

There’s also the argument that much of U.S. Conservatism is premised on Postmodernist thinking, that their perspectives are equally true as others. However, Postmodernism is not saying that all perspectives are equally true, but that all perspectives are worth considering to be true.

The most important insight behind the Postmodern critique is that grand theories don’t exist, and that categories must be carefully constructed, since there is power behind the very choice of categories. At its best, it is the recognition that society is behind everything, and one is always confined by society. At its worst, it is a dismal reality with no truth whatsoever.

Post-postmodernism or Metamodernism?

Some have proposed that we have already left behind Postmodernism. We might be in the metamodernist age? That is where we understand there is societally contingent truth, and we simply choose not to care and oscillate between categorizing and theorizing, then critiquing those categories and theories, and continuously redoing this process.

Maybe.

This self-referential process is reasonable, and I agree rejecting the abject Nihilism of Postmodernism at its worst is good. In this way, Post-postmodernism or metamodernism, or whatever it will be called, may draw upon the best of each movement.

Theory After the 80s

What does this mean for us? If you believe in science and theories and such, that’s fine, but you cannot meaningfully apply them to anywhere without understanding the alternative perspective. Since the 80s, Postmodernism has challenged us to critically question concepts we have taken for granted all of our lives, whether that is age, gender, sex, sexuality, race, class, age, etc. There are no grand theories, no overarching external consistency. Be specific, and above all listen and consider power imbalances. While not all perspectives will be equally right, all perspectives deserve to be considered equally.

Is that not freeing?

P.S. Social Constructivism

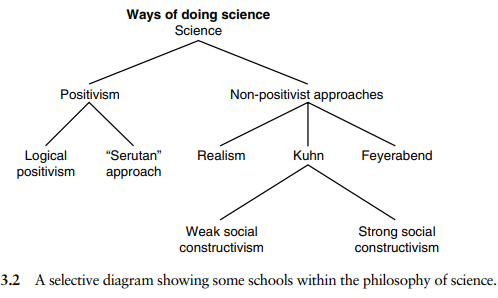

I thought it’d be nice to show off the analytical strength of a Postmodernist idea. One of the better ideas to come out of it is social constructivism. Basically, social constructivism is the belief that society shapes what is considered true or not, what is considered factual or questionable. There is weak social constructivism, where it is believed society constructs what is or isn’t true over objective truths, while there is also strong social constructivism, where it is believed society constructs truth itself.

At least in some cases, strong social constructivism probably applies. For example, race is definitively a social construction, descended from ideas from Spain and slavery in the Americas. Race did not exist prior to the 1600s. It is a construction out of the idea of definitive, insurmountable difference between groups of people, where prior there were more flexible forms of membership in groups. It was the result of a concern to preserve power, as demonstrated by racism’s strength in sabatoging Reconstruction after the U.S. Civil War. There is nothing true about race. Most of the genetic ancestry testing and medicine’s use of race is falsified, misguided, or just untrue. For example, China is so large, and the history so complex, that southern China’s genetics are noticeably different from northern China’s genetics. Yet these are grouped together as Chinese for some reason. Genetics follows clines, not races. Race is too diverse a category itself to be an accurate judge of medical or genetics. Race is purely cultural, not genetic.

Medicine’s use of race as a proxy, therefore, is terrible and probably kills some people every year, especially in communities who are marginal in the categories imposed upon them. For example, Asian usually includes Pacific Islanders, but Pacific Islanders may have different enough genetics (broadly speaking) that they should be considered separately to understand their specific medical problems. This has real harm, for instance in ignoring the excess of Pacific Islander death from the COVID pandemic, due to a high number of nurses being from or descended from the Phillipines. Besides, epigenetics means the environment can affect the genetic code now, so all of the genetics testing that is done might be useless for understanding much about someone’s potential medical afflictions, without more specific tests.

P.P.S. Paywalled Sources

Some sources I have linked are paywalled or hard to find. If people would like an explanation, summary, overview, or help hunting them down, please ask me in the comments and I will do that.

-

This is not a one time mistake. He has followed up with other terrible ones like Collapse. ↩︎

-

This is an uncritical view of Modernism. The very categorization of Modernism might need dismantling since this groups together too many disparate and different ideas such as Existentialism, Fascism, Communism, Social Darwinism, etc. ↩︎

-

At the least, it should seek to do such things. Diseases like Polio are truly horrible, and eradicating these and others to the best extent medicine is able to can only be considered a good for this world. ↩︎

-

I don’t believe this since it would be a dismal conclusion, but also because Quantum Mechanics is not yet axiomatic, so it’s not purely mathematical. That means the theorem doesn’t apply. ↩︎

-

See Kofman, Ava, 2018. “Bruno Latour, the Post-Truth Philosopher, Mounts a Defense of Science”. ↩︎

-

This refers back to aforementioned Jared Diamond. He won a Pulitzer, but a Pulitzer only has merit in literary accomplishment. A Pulitzer means nothing in the fields of History, Sociology, Anthropology, and any other social science. His Guns, Germs, and Steel has so many issues that there exist articles such as F**k Jared Diamond out there that castigate him. In Native American studies, his books have been considered some of the worst damage ever done to the field. And as I’ve said before, it’s not a one-off. Collapse was insulting in just its first chapter. He tries to describe societal collapse, but then he includes the U.S.S.R.’s collapse as an example, which violates his own definitions. There are many books that were written in response to Diamond, that essentially say that there’s no theory of collapse, because collapse itself doesn’t really exist. The Roman Empire’s west fell, but the East survived almost until the 1500s. They were called the Byzantine empire, but they referred to themselves as Romans still. The Han dynasty ‘collapsed,’ but almost immediately there were the states of Wu, Shu, and Wei to take its place, with no loss in culture or technology. Some groups may have abandoned their urban locations like the Indus Valley Civilization or the Mayans, and some places their states ‘failed’ but there probably wasn’t a widespread free-for-all for blood or mass loss of life, but something far more gradual. ↩︎

-

The classic is Mutual Aid, something I still need to read, though I understand its significance. Something more concrete is eusocial insect species, like ants or wasps, who are at the top of the food chain because of their cooperation. ↩︎

-

There are problems with this definition. Again, like Modernism, Postmodernism groups together many ideas, some of which question the very idea of categorizing. ↩︎

-

See The Invention of Women by Oyeronke Oyewumi. ↩︎

-

Look up the Himba tribe color experiment. ↩︎

-

See “Diaological Epistemology” by Nira Yuval-Davis. ↩︎